This talk/presentation was incredibly exciting to attend to. I was able to listen to the artist’s ideas behind the pieces I really enjoyed at my visit to the Women in Focus exhibition. I also found it helpful for my own work, as the female artists described how they’re interested in photographing young girls and watch their confidence grow as time goes by, and to also create this work in very rural areas of South Wales where a sense of community is still thriving.

Category: Contextualisation (Second Year)

Third Year Exhibition

The third year’s exhibition was incredibly inspiring and all-round amazing to view. I especially enjoyed looking at the Maker exhibition, as they used incredible lights and creative shapes to display them. I found the piece by Amy Perry haunting to look at (below) which looks into the barrier between the body and the spiritual realm we inhabit, that we are not our bodies because they’re only temporary, and instead, we are our spirits.

Grace Cupper in Fine Art had a piece up titled ‘A Self-Portrait In Pink’, which is an installation that uses the materials around her – discarded boards, sketchbook pages and the studio walls – that reflects her thoughts, experiences, dreams, environment, emotions and coping mechanisms through immediate recording.

Here are other pieces I found wonderful and thought-provoking;

Valie Export – Linz, Austria (b. 1940)

Until the age of 14, Waltraud Lehner was educated in a Vienna convent. As she grew up, she became immersed in the film industry, got married and became a mother. It wasn’t until 1967 when she adopted the pseudonym VALIE EXPORT, both an artistic identity and a personal brand, one that simultaneously rejected the command of the men in her life and challenged the Nazi ideology of her parents’ generation. Her last name was, in part, a tribute to a brand of cigarettes.

“I did not want to have the name of my father [Lehner] any longer, nor that of my former husband Hollinger,” EXPORT explained in a BOMB interview, “My idea was to export from my ‘outside’ and also export, from that port. The cigarette package was from a design and style that I could use, but it was not the inspiration.”

EXPORT’s work in video, performance, photography, sculpture, and computer animation, often critiqued the way commercial film and the mainstream media objectified the female body. “In order to achieve a self-defined image of ourselves and thus a different view of the social function of women, we women must participate in the construction of reality via the building blocks of media-communication,” she said. “This will not happen spontaneously or without resistance, therefore we must fight!”

For the piece featured above, 1968’s “Tapp und Tastkino [Tap and Touch Cinema],” EXPORT crafted a wearable theatrical stage and wore it on the street. She then invited passersby to stick their hands inside the stage and feel, without looking, her breasts. The piece examined the underlying relationship between violence and eroticism, seeing and feeling, private and public. I found this linked with my final piece, but instead of letting hands get into my box, I will be ‘safe’ from the violence highlighted in this piece.

G39

In G39 this afternoon, I was able to see pieces by artists such as Anna Grace Rogers, Gweni Llwyd, Mark Hicken, Heledd Evans, AJ Stockwell, Thomas Williams, Elin Meredydd, and many more.

They made collaborative work based off of their time in Venice;

“There is a difference between visiting a place and living in a place. When visiting a place, everything becomes exotic, its otherness is made more tangible by our fleeting experience of it. For a short amount of time our rituals and habits and ways of being that tick-tock our everyday lives are replaced. In this new place we sleep at different times, we eat different food, we look at the world differently. Venice is an oasis, a mirage, a shimmering watery floating/ not floating place of looking seeing smelling and experiencing life differently. It is all there for our consumption – for a short amount of time before we turn and leave it.

But being there for a job, for an extended period of time, its customs become ours. We experience Venice in new ways. We are neither natives or tourists anymore and our passage through the city is irritated by the slow-gazing, bridge-stopping drift of sightseers that we were once a part of. We need the launderette, to get to work, and to move more efficiently. We wake up there. ”

In May 2017 the Wales in Venice exhibition, James Richards: Music for the gift curated by Hannah Firth was launched. g39 has been working with the group of artists, writers and curators who were invigilators at the venue in Venice for the length of the show. They have been immersed in the show, keeping everything going, speaking to visitors, and locals, responding to the culture, language, history, the city of Venice, James’ show and the other Biennale exhibitions.

They have also been spending time in Venice developing new work and research and we have invited them to present it at g39. The works here will interact with each other; rather than stand on their own, the collection of individual objects becomes one overarching experience.

It has been curated as a varied collection of artworks, artefacts, objects, sounds and actions and research, where each occupies the same space. Reflecting on an eclectic and domestic curatorial approach they’ve created a model of the artists shared domestic space as a framework to combine and assemble the work. This is a replica of the space where the invigilators lived, on the strange isle of Certosa in the Venetian lagoon.

Certosa is an Italian word meaning monastery, or charter house. The Isle of Certosa has little of the grand historic architecture associated with Venice and, apart from a hotel (and marina), there is nothing there for tourists or sightseers. The isle has its own strangeness, isolation and peculiar character that feel neither contemporary nor steeped in history.

Every two years Venice is the host to the Wales pavilion at the Biennale, a part of life here is transplanted there for the duration of the Biennale, still one of the cultural markers of the year for curators, dealers and artists. What is often overlooked is that Wales is also growing a relationship with a space, with a community there and with Venice itself. After the first wave of Biennale guests leave, the people local to the venue come to see the work, come to see the buildings that are theirs and continue an ongoing dialogue with Wales through the live-guides.

Annie Sprinkle – “Public Cervix Announcement”

In this performance piece, Sprinkle invites the audience to “celebrate the female body” by viewing her cervix with a speculum and flashlight, proving her to be a sex-positive feminist, as she once described herself. She wanted to do this because people know next to nothing about female genitalia, therefore used herself as an example for people to learn. This attitude towards sex, to me, is an extremely positive one. She shows sexual confidence and created an iconic change in the way many people viewed women’s bodies by using humour during the Post-Porn Modernist era. In the words of actor, performer, and researcher Igor Leal, post-porn is “a movement based on sexual expression, in which the sensations and possibilities of the body are expanded”. This expansion is realized mainly by shifting away from pleasure focused on the genitals and toward full bodily pleasure, taking the fluidity of pleasure into account.

I find this piece extremely interesting – her sexual confidence and trust in her audience is inspiring, and I’m aiming for the same response. This also links to my site venue locker exhibition where I made it so that the audience had to open up lace curtains to enter the inside of a vagina-type instillation of a sex worker’s room. However, I’m especially interested in how and why she used herself, leaving herself open to being objectified. We see that because she was the one leading the performance, she was the one in control the entire time, making this a powerful statement against the male gaze by making it and educational piece. I think that her fetish clothing either reflects her being a pornstar in the past, which would be empowering, as I believe that sex work is work. It could also be seen as ironic using sexually provocative clothing for a performance that was for educational purposes only adds to her humorous personality, especially knowing it’s an alter-ego she’s made up that makes her more sexually confident.

Lynn Hershman Lesson

W.A.R. (Women Art Revolution)

Lynn Hershman Leeson creates a monument to all the women who have changed the world of art since the 1960s as artists, curators and critics. The film is composed of film clips and interviews that Hershman Leeson has collected over a number of decades. Alongside important artists such as Yoko Ono, Yvonne Rainer and Carolee Schneemann, women in the museum business are also featured. Starting from portraits and film clips on the political background, the film tells of the struggle for the recognition of female artists in the second half of the 20th century.

I was especially inspired by Yoko Ono’s piece, “Cut Piece”, 1964, and Marina Abramovic’s “Rythm 10”, 1973. In Cut Piece, one of Yoko Ono’s early performance works, the artist sat alone on a stage, dressed in her best suit, with a pair of scissors in front of her. The audience had been instructed that they could take turns approaching her and use the scissors to cut off a small piece of her clothing, which was theirs to keep. Some people approached hesitantly, cutting a small square of fabric from her sleeve or the hem of her skirt. Others came boldly, snipping away the front of her blouse or the straps of her bra. Ono remained motionless and expressionless throughout, until, at her discretion, the performance ended. In reflecting upon the experience recently, the artist said: “When I do the Cut Piece, I get into a trance, and so I don’t feel too frightened”.

Abramović’s first forays into performance focused primarily on sound installations, but she increasingly incorporated her body – often harming it in the process. In Rhythm 10, she used a series of 20 knives to quickly stab at the spaces between her outstretched fingers. Every time she pierced her skin, she selected another knife from those carefully laid out in front of her. Halfway through, she began playing a recording of the first half of the hour-long performance, using the rhythmic beat of the knives striking the floor, and her hand, to repeat the same movements, cutting herself at the same time. She has said that this work marked the first time she understood that drawing on the audience’s energy drove her performance; this became an important concept informing much of her later work.

Making themselves their own victims and open to abuse is very uncomfortable to watch, but I think it’s extremely important that pieces like these exist because of how much I related to their situations, knowing how vulnerable their bodies become. Ono’s piece leaves the audience in control, showing confidence and trust, whereas “Abramović’s art comes from trauma and the body’s relationship to the state” (Dr. Kristine Stiles), proving how violent and vulnerable women’s art is, and how embodied it is in feminist art. Moving away from violence, trauma and anger, which are all rightfully felt by women artists, I want to use the negative experiences I’ve ever faced for being a woman and throw it back at our patriarchal society by using some humour, as Marcia Tucker said in 2006, “humour is the single most subversive weapon we have”. I’ll be doing this with nipple stickers with the words “fuck me” on them, holding a large clay and exaggerated vagina, symbolising what I’ll be metaphorically selling, which no one will be able to touch me, still making me completely in control of the situation.

Interesting artists at the National Museum Cardiff and Chapter

I was invited to participate in a talk about James Richards’ pieces at the Chapter Gallery through the medium of Welsh, and having already seen it before in Venice, I was very excited to see how a different setting for the films would change how I felt about them. I made a short video below of the parts I found especially interesting;

What I found was that I felt less uncomfortable seeing it for the second time because I already knew what was in the film and what was coming next. Because of this, I was able to understand what it could be all about more. I personally thought it was about time, hearing the ticking clocks in the background, dancing skeletons and a man going through vintage-looking photographs, which certainly made me feel nostalgic. The fact that the films are now shown in a dark room at Chapter and not a romantic old Venice building changed the atmosphere, too. I found it made it more serious in a way being in a dark room, because I was never tempted to look around at old architecture.

I visited the National Gallery again to view the contemporary art currently on display by artists such as Anthony Stokes and his photography. Writing about his pictures in his book, Anthony says: “I’m lucky to have caught this profoundly important place in Wales – the power-house of the Industrial Revolution – at a time of quickening change. But its essence seems to remain intact. Only notions of conventional good taste, or coastal prejudice, are capable of obscuring the wonder of The Valleys. Could you trust a painting or a verbal description to tell the truth? Might a camera be the perfect tool to reveal such beauty?… I’m not fond of any kind of picture, including portraiture and landscape, where the subject is seen through rose-tinted glasses. I want the truth, in its entirety. Apart from having a likeness, good portraits reveal something else of the sitter: a quirk, a beauty, a characteristic trait – or something potent you can’t quite place. They are personal.”

I find the honesty in his work refreshing – he just takes pictures of the truth of the Welsh Valleys, which is something I value because rural areas, such as where I live in North Wales, are often sold as magical places (which is certainly true, in my biased opinion), but the truth of the industrial, poor past is rarely shown.

Politics – Plaid Cymru talk

Plaid Cymru Leader Leanne Wood visited Cardiff this evening to set out a radical agenda for ensuring that decisions affecting Wales are made in Wales through a programme of democratisation and empowerment. Leanne spoke about how to challenge London parties’ top-down, state-centric politics and heard from us, the people in the area, about our aspirations for Cardiff and Wales.

I was able to hear and talk about many different things that will be happening across Wales in the near future – many things I wasn’t too happy to hear. Getting involved into politics, especially local politics, is incredibly important for my art. I like to gain a lot of knowledge for what I speak about and, more importantly, get involved. Wood often speaks about liberal matters, such as feminism, and speaks against the far right, especially when it comes to oppression against minority groups, which I find important to debate against in my art, as well as publicly.

Guilia – Porn and architecture

Brooklyn-based artist Giulia is an artist merging “sexy” images of the female form with beautiful images of outstanding architecture. The outcome simultaneously explores the realms of pornography, geometry and art.

Having grown up ashamed of her curves, Giulia is using the project as a way to fully appreciate the twists and turns of women as a whole, similarly to the way we would with any good design. Giulia strategically places architectural elements over images of women, keeping the highly allusive element alive while mostly bypassing Instagram’s strict policy on nudity. She tells Highsnobiety: “It started with me creating random pornographic collages where I would replace genitalia with images that looked phallic or yonic, typically food.” She explains this slowly evolved into the process of her looking for any images that resembled the female body, eventually being refined to just architectural images that resembled the female form. Here are some examples below;

As a voice for pro-sex and pro-open expression, Giulia’s found a hugely creative means to connect the dots. Noticing architectural design queues featuring angles that mirror those of a familiarly feminine form, she’s making a comparison to our bodies being functional art.

Turning these pornographic pictures of women and of sex, something most of the public wouldn’t find pleasing to look at, into collages of beautiful architecture is tremendously clever, and I find that this idea links to the clay vaginas I made that resemble flowers. Making the frowned upon aesthetically pleasing is very interesting to me, and I’m interested in creating more artworks around this idea in the future.

Women in Focus – National Museum Cardiff

Women in Focus is a year-long exhibition that explores the role of women in photography, both as producers and subjects of images. The exhibition draws on works from the permanent photographic collections at Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales and comprises two parts:

Part One: Women Behind the Lens celebrates the role and contribution of women throughout the history of photography, from the first pioneering women photographers in Wales, Mary Dillwyn and Thereza Mary Dillwyn Llewelyn, to emerging contemporary practitioners including Chloe Dewe Mathews, Bieke Depoorter and Clementine Schneidermann.

Part Two: Women in Front of the Lens explores the representation of women as subjects in photography, from intimate and playful 19th century staged family portraits by John Dillwyn Llewelyn and Robert Thompson Crawshay, to more contemporary depictions that capture the innate beauty of womanhood. Part Two also seeks to examine how photography has been used to mis-represent women through direct or indirect objectification, an issue that has particular currency in today’s climate.

Women in Focus has been programmed to coincide with the centenary of the Representation of the People’s Act 1918, which enabled some women over the age of 30 the right to vote for the first time. This Act marked a key moment in the fight for universal suffrage.

I visited the first opening, Women Behind the Lens, that only just opened a few days ago, which really moved me and had me thinking about my own work, since I use myself as an object in my work, and I thought about what impact it’s meant to have and how the meaning would change if I used someone else. I wanted to look into these artworks further, therefore I booked to go to a talk with one of the photographers in June, Clementine Schneidermann, who’s artwork is below;

In 2015, French photographer, Clementine Schneidermann, undertook a six-month artist residency in Blaenau Gwent. She began working with children from different youth groups across the area in collaboration with independent stylist, Charlotte James. Three years on, and with the same collaborators, Ffashiwn continues too evolve and offers a thought-provoking and tender portrayal of childhood, identity and community life in the South Wales Valleys.

These two pieces below, one by Bieke Depoorter (1986) called Untitled from the series I am about to call it a day, and the other by Susan Meiselas (1948) called Dressing Room 1 from the series Pandora’s Box, were my favourites from the show. The dim red light that just barely lights up the silhouette of the woman is something I’d like to recreate in my final piece. The photographs from the series are predominately made inside the homes of her subjects and are charged with a vulnerability and an intimacy. Depoorter claims that intrinsic to her practice is the fact that she spends the night at her subjects’ homes. I’m fascinated by this idea, as it links to my invasive theme, and I will look further into it for my piece by perhaps using the idea of invading someone’s privacy by using a window that someone will have to look through to look at me. The second, by Susan Meiselas, also feels intrusive as we peer into a young woman standing topless, but her face is hidden behind a wall, not revealing who she is. Meiselas works with human rights, especially women’s rights, and made work about her visit to Juárez (1998), where between 99 and 109 women had been raped and murdered in and around the city. To the outrage of feminist groups, local authorities suggested that the women provoked the attacks by frequenting bars and wearing short skirts. This type of experience and research is definitely influential to my work and sex worker’s rights, and motivates me even more to make work about objectification and based the safety of women wearing ‘short skirts’.

Here are the other images curated around these pieces;

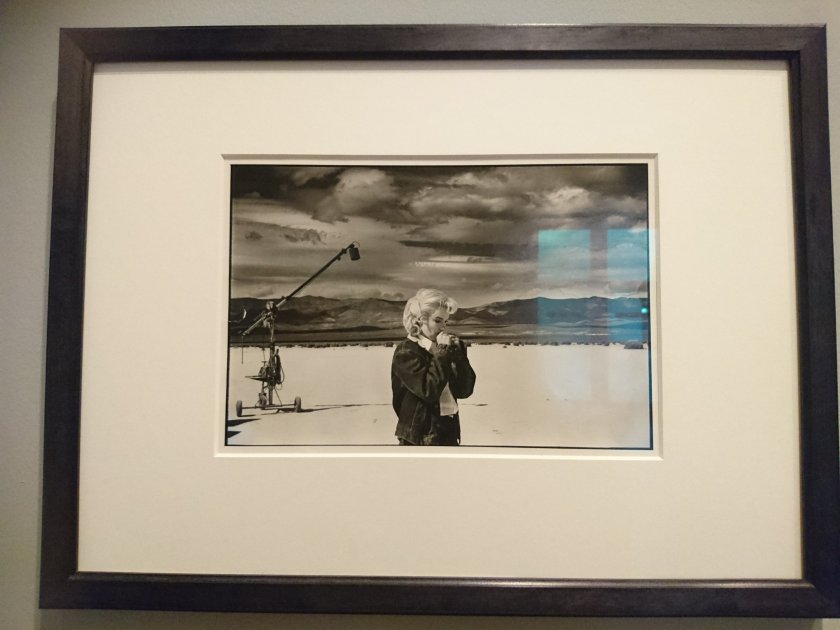

I found this image of Marilyn Monroe on the set of The Misfits in 1960 compelling, photographed by Eve Arnold. Arnold was the first woman to join the prostegious Magnum photo agency in 1957. She had an extrordinary career as a photo-journalist. She moved skillfully between documenting the everyday live of ‘the poor, the old, and the underdog’, and the glamorous lives of the rich and famous. However, she is perhaps best known for this sensitive portrayal of Monroe, with whom she developed a close friendship. The photograph was taken on Monroe’s last completed film before she died in 1962. The film was plagued with challenges from the outset, amongst which was the breakdown of Monroe’s marriage to Arthur Miller, the writer of the film, making the photograph powerful in the sense that it captures Monroe, an iconic sex object, known for her confidence and sexuality, during a very vulnerable time that ultimately lead to her premature death.

I also found this piece of young women gathered around topless, but holding their breasts thought-provoking. Photographed by Siân Davey (from the series Martha, who is her step-daughter), I find it interesting how a group of young girls, whom I interpret as friends, have the confidence to strip down to their knickers, yet cover their breasts. Davey was a psychotherapist for fifteen years and uses this experience in her photography. Her personal stories and tender portrayals explore the complex and intimate relationships that exist between a parent and a child.

Here were some of the other artworks that caught my eye;